Out of nostalgia, I recently picked up the DVD collection of the original six Tarzan movies, filmed in the 1930’s and 40’s, and starring Johnny Weissmuller as Tarzan and Maureen O’Sullivan as Jane. So far, I have watched the first three films in the series:

Tarzan the Ape Man, Tarzan and His Mate, and

Tarzan Escapes. I can remember watching these movies as a little girl on Saturday afternoons on TV. I was as fascinated by Tarzan’s strength and form then as I am now, though I didn’t fully understand the attraction. Tarzan was beauty and power. He was protector and provider. He was innocence and virility. He was rescuer and fighter. He was companion and lover. He was man in his natural, unblemished state. And Jane was destined to join him in his primitive world. Some people might think the stories are corny, and I’m sure they strayed from Edgar Rice Burroughs original novel, but the films were an ambitious undertaking, with unbelievable stunts, impressive athleticism, and groundbreaking cinematography.

There is of course rampant racism in the films. At one point in

Tarzan the Ape Man, Jane vouches for Tarzan’s humanity by saying “he’s white,” but this article will not be about the racism in the Tarzan films. Just know that it is there, that it is a reflection of the times in which it was filmed, but let it not overly mar your viewing experience. After a brief National Geographic style introduction, the most favorable portrayal of the Africans is that of superstitious slave-like porters. The least favorable are the opposing savages who take thrill in the torture and killing of others. Only one black actor has a role of any consequence, and that is the character of Saadi the overseer in the second film,

Tarzan and His Mate. He sacrifices himself to save a box of ammunition for the white hunters. Strangely enough, the actor returns from the dead in the third film, but this time with the name of Bomba. (This also happens with the bumbling Australian hunter Beamish, who returns two years later with the new name of Rawlins.) Alas, Saadi/Bomba has lost most of his moral fiber as he sells out the white tourists to a savage tribe.

Like the red-shirted guy in Star Trek, you know most of the black guys will be killed off in each movie, at first by falling off the dangerously high and narrow pathways of the Mutia Escarpement, or eaten alive by an alligator, or shot to death for insubordination. The rest usually meet a gruesome end at the hand of savage African tribesmen. The white woman in the film always cringes to see such deaths, but more out of squeamishness and fear for her own safety than any sympathy for the poor African.

At times the acting and special effects can come across as a bit hammy to the modern viewer. The damsel in distress emoting seems right out of silent film, but then again, these films are right out of silent film. The style of acting was probably what the audience expected. The special effects are actually quite fascinating and ambitious given the technology of the day. Some of the animals are real and interacting with the humans on the set. To see them on the screen must have been a real treat for the movie-goer. Tarzan is shown wrestling a wildebeest and several large cats. The animals are live, at least in some of the shots, but there may be a stunt double in Tarzan’s place at times. The documentary included with the DVD’s will hopefully tell. In one laughable scene, Cheeta, usually a real chimpanzee, is supposed to hold onto Tarzan’s back while he swims across the lagoon, but he is replaced with a puppet that jerks stiffly from side to side as Tarzan swims. Puppets are used in other scenes, sometimes as animals with real people, and sometimes as people with real animals. Most of the puppets are obviously fake.

Raging hippos attack the white hunters and herds of zebras run through the set. There is one scene with a close-up of a zebra, and a part of me is wondering if they used a painted donkey in a zebra wig. Maybe it was just a zebra with a lot of personality.

The wildebeest incident is particularly interesting in that the same footage is used repeatedly. In this scene Tarzan goes out to fetch dinner as if he was going to the grocery store. He wrestles a passing wildebeest to the ground, breaking its neck. As he is stripping a large piece of flesh from the carcass, he is interrupted by a hungry lion. Apparently not wishing to fight over dinner, Tarzan quickly leaves, steak in hand. You’d think eventually the wildebeest would learn they are a walking supermarket.

Crocodiles figure largely in all of the films. There are several shots of real ones slithering into the water and a well-known scene where Tarzan wrestles an unbelievably large one. The filmmakers liked the scene so much, they used it in more than one film too.

Tarzan lives with a group of chimpanzees, the ones who presumably raised him, though the backstory is not provided. Some of the apes are convincing actors in costume, and some are real chimpanzees. He’s on friendly terms with the elephants as well, helping them out and occasionally hitching a ride on one. Some of the elephants are on the set, though some scenes incorporate stock footage, and some scenes are reused. (Why waste film?) The apes and elephants come to his aid whenever he calls, to fight off savages or crush villages. Tarzan is truly the king of this jungle.

As blue screen technology is a long way in the future, all of the charging animals are stock footage projected on a backdrop. In some shots the projection is three dimensional, showing the charge from the front, overhead, and the back. The actors and the filmmakers do their part to make the scenes as convincing as possible. I’m sure the target audience was suitably thrilled. I know my kids, more used to the slick production in the likes of

Harry Potter or

The Chronicles of Narnia, were just as enthralled with the Tarzan movies. They didn’t even ask why everything was gray.

Many of the scenes are quite spectacular, fake animal or not, and Olympic champion Johnny Weissmuller is to be commended for his skill. There is enough movie magic to keep even a Peter Jackson’s

Lord of the Rings fan transfixed, so that the film at least deserves a place in movie history for its ambitious if occasionally cost-effective methods. Without such films as

Tarzan, we might not have ever seen a

Star Trek, or a

Star Wars or an

Indiana Jones.But the film is not just special effects. It is first and foremost a love story, albeit one set in a jungle paradise, with wild animals and savages and scheming white hunters. When Tarzan first sees Jane, played by Maureen O’Sullivan, in

Tarzan the Ape Man, he has never seen a human female before, or at least not a white one. He is fascinated, and deftly steals her away from her father and his company to take her back to his lair in the trees. Jane is of course frightened and does a lot of screaming and flailing about. Jane is sure that this mostly naked brute has only one thing on his mind, to steal her virtue and have his way with her. She quickly realizes that he doesn’t speak, at least not English, which only adds to her fear. Now she is captive to a naked, dumb, sexually-deprived brute.

But Tarzan surprises her. He watches Jane struggle somewhat dumbfounded, as if he doesn’t know what to do with her anyway. After a few minutes, he leaves her there, and settles down to sleep on a nest of branches, stabbing his knife into the wood first, and then clutching the handle as he sleeps. Jane peeks out, surprised by this turn of events. Jane seems reassured that the brute has a tender heart, and she does not try to escape. Perhaps she is reassured that he means her no harm. Perhaps she is intrigued by this wild man.

Jane’s companions eventually find her, and I wonder to myself if they question her virtue at the hands of the savage. In the ensuing rescue, a female ape is killed, possibly the one who raised Tarzan, and he lets out an anguished cry. This confirms for Jane that the brute feels love, and now they have invaded his paradise and brought him sorrow.

After the rescue, the white hunters decide to search for Tarzan. One of them shoots him, and he staggers off injured while Jane is taken by the apes. Lions attack the injured Tarzan, and he is barely able to fight them off. Eventually he is rescued by a friendly elephant, and the apes bring Jane to Tarzan. She nurses him back to health, conveniently ripping her clothes to make bandages. There is a good deal of flirting and swimming about the lagoon as he recovers. We know that Jane has given in when Tarzan picks her up and she lays her head on his shoulder in quiet acceptance. Fade to black.

Jane is remarkably happy with her jungle lover, but when her father finds her, she feels she must leave. Jungle adventures abound. Pygmies, who are really Little People, that is, genetic dwarves, in black body makeup, kidnap our white adventurers and their African laborers. Tarzan must rescue them of course. When it’s all over, Jane realizes that she must stay with Tarzan. When her father tries to convince her that he belongs to the jungle, she tearfully blurts out “Not now; he belongs to me!” She stays behind when her other companions leave.

If Jane is the worldly Eve, then Tarzan is the tempted Adam. In Tarzan’s world, he has long been the only man, and all the animals are at his command. He eats the fruit of the trees, and the flesh of the beasts as needed. He lacks only one thing, and that is a female companion. Tarzan and Jane are primal lovers; their home a Garden of Eden in an otherwise forbidden land. Evil lurks vaguely on the perimeter. Jane’s white associates repeatedly try to upset the delicate balance. Each time, Tarzan and Jane affirm their devotion to each other against the outside world.

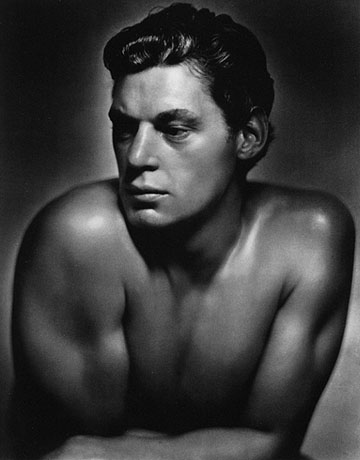

The female viewer of the Tarzan films gets an uncommon treat as Tarzan swings, flips, wrestles, runs, leaps, and swims through the jungle. Occasionally he mopes about pining for Jane. And he does all of this in a teeny loincloth. His physicality fills up the screen and captivates the viewer. Johnny Weissmuller, fresh from an Olympic career that included five gold medals and broken records in every event he entered, was embarking on a modeling career when he was cast. His only prior screen experience had been a small role in 1929 when he appeared clad only in a fig leaf. He was 28 years old when the first film was released in 1932. He proved to be very popular with the ladies.

In the second film,

Tarzan and his Mate, we are also given the full benefit of Jane’s emergent sexuality. Though she was flirtatious and proper in the first film, now she has unashamedly abandoned herself to the sexual pleasures available to her. She wears a loin cloth that is even teenier than Tarzan’s, little more than a flap in front and behind connected by a narrow cord. Her top is a sort of midriff-baring bra. In this film, one of her former companions and another hunter try to find her. They bring her the latest fashions to entice her to return to civilization. She quickly dons the silk stockings and a beautiful evening gown that is very nearly backless with a plunging neckline even more revealing than her usual bra. The dialog is sexually loaded, with the white hunters joking about her revealing mode of dress, and Tarzan very obviously turned on by the new stockings. The scene ends with Tarzan carrying her off, obviously to have sex, though of course, that is not shown. They wake up side by side the next morning, Jane naked under an animal skin and the evening gown adorning their shelter like a swag. She puts the dress back on, feeling a need to dress properly now that there are other people around, and they go out for their morning swim.

Jane’s famous, or infamous, nude scene comes up next. Tarzan pulls off her dress as she dives into the water. They then proceed to swim a graceful underwater pas de deux. Underwater, Jane is as naked and graceful as any odalisque ever painted by a master. Cut from the release of the film and restored only recently, the scene is both beautifully filmed and shockingly avant-garde. It’s gems like this that make the film worth viewing. The skimpy clothing, the morning-after scene, and the underwater nude scene aren’t there simply for titillation. They indicate Jane’s new status as wife and lover. Jane even teaches Tarzan to call her “my wife.”

The teeny-weeny loincloths and nudity were not to last though. With the implementation of the Hays Code for the third film,

Tarzan Escapes, Tarzan’s loincloth provides a bit more coverage, though it’s still daringly high-cut. Jane’s loincloth and bra have been replaced by a high-necked mini-dress with only her arms and legs exposed. Inexplicably, the first and third films are on the same DVD, so I actually watched #3 before #2. It was interesting to watch the clothes expand and shrink. You can also tell when footage from the earlier films is repeated in later films by checking out the width of Tarzan’s loincloth.

Tarzan and Jane repeat their underwater ballet in

Tarzan Escapes, with Jane clothed this time, since it was cut from the prior film. The filmmakers then take their revenge on those who thought the second film was too racy by filming the most suggestive sex scene yet. Whereas the sexual encounters in the previous films were merely implied by the slightest glance or movement, here the director wordlessly lingers over the jungle couple, each shown from the other’s point of view. After a playful swim, Jane reclines on the bank of the lagoon. Tarzan plucks a water lily and gives it to her. He climbs out of the pool and stands over her. His expression changes from happiness to desire, noticeably enough that my six-year-old daughter commented on it. The camera switches to Jane, bathed in radiant light, her lips parted and moist as she gazes upon Tarzan. The camera pans to her face, and then follows her shoulder and arm as she releases the flower back into the water. Fade to black.

Give me a moment.

Ok. Johnny Weissmuller’s Tarzan was imprinted on my brain at a young age, but that doesn’t mean I wanted to grow up and live in a tree house with a wild man. Even if I could manage that, it would be hot and sticky, the bugs would eat you alive, and I’d grow tired of killing and skinning my supper. Eventually I would long for some good conversation and culture. Meanwhile rebel militias, slash-and-burn farmers, and land developers would encroach on our jungle paradise. So keep the jungle fantasy on the screen, where the annoying realities of life can be kept at bay.

There is an innocence to the Tarzan films, a belief that the worries of the world can really be put aside. Even in this world, the occasional cannibal or white hunter comes along to try to ruin everything, but it all gets neatly put back into place. There is plenty of violence, but it’s the sort that seems to go with movie adventures. A remake would risk making it too gory or moralistic.

Greystoke notwithstanding (maybe I should watch that one next), it’s ripe for updating with a light-hearted nostalgic touch like the

Indiana Jones movies or

Star Wars serial. Taking out the racist overtones is a must. Correct some continuity problems. Improve the biological accuracy, that is, put plains animals on the plains, and jungle animals in the jungle. Leave in the live animal wrangling where possible because it’s part of the charm of the original movies. Augment with CG to replace those projected back drops, but keep Tarzan as real as possible.

For me, no one can improve the portrayal of Tarzan and Jane. Johnny Weissmuller was cast more for his looks and athletic ability than his acting, but the part calls for an unsophisticated, strong, silent type, so it works. Maureen O’Sullivan does most of the talking for both of them anyway, and delivers some classic lines. Their chemistry and their grace more than make up for the complete improbability of the whole situation. For two hours you can believe that love can create a sanctuary in the midst of a mythic jungle. For two hours you can believe that love can create an intimate connection between two people that transcends distance. For two hours, you can believe that love conquers all enemies and vanquishes all ills. For two hours, you can believe in love.